Thursday, November 20, 2008

Maude in the morning

Morning is her time. I watch this over and over when I am away from her at school.

Friday, November 07, 2008

the other hand

A reader who voted for Amendment 2 in Florida, the one banning same-sex marriage from the state constitution, left a comment on my last blog post. As I struggled to respond, I realized it might be better to post what I was thinking on the main blog rather than get steamed in a footnote. I am also reposting the comment, since some people read on a blog reader that doesn't have access to comments, and might not know what the heck I I am talking about.

The jist of the comment they left was that they voted as they saw fit, and it was just an opinion. They also said nice things about the blog and added that they thought some day very few people would agree with their position:

"Hi,

I voted for Amendment 2, to maintain marriage as between one man and one woman, but it is not because I fear LGBT nor hate you nor fear you nor am I ignorant of the issues. It was a difficult decision because I DO understand the issues, but still, I felt that it was the right way to vote.

I'm not writing to anger you or upset you in any way, but rather merely to say, that a vote for traditional marriage is not necessarily one made out of hate, fear, or ignorance. It is simply based on a differential in values.

Thanks for writing your blog and sharing your sentiments. For whatever it is worth, I'm sure that one day, probably soon, those that share my views will be in the minority and those that oppose them will win the majority."

The first thing I have to say is that I just don't know how to be dispassionate about Florida right now. Florida is one of the most hateful states is a sea of red Southern states hostile to LGBT rights. Florida is the only state in the entire country to explicitly ban "homosexuals" from adopting children. They aren't even sneaky about it, like Arkansas or Utah--states that get away with discriminating against gay adoption by banning unmarried people from adopting children, then banning gay people from getting married, thus effectively banning gay people from adopting children. Florida is right up front about its bigotry--even though it means many children who otherwise would have legal parents will instead languish in the foster care system. Florida already bans gay marriage with a Defense of Marriage Act--a mini-DOMA modeled on the federal one Bill Clinton signed into law in 1996--and now, with Amendment 2, is enshrining this ban into the state constitution.

Just An Opinion, I'm glad you left a comment. I'm sorry you voted for Amendment 2, though I appreciate your honesty. I wish your vote had been only "a vote for traditional marriage," as you say it was. I wish it had been only an opinion. But it wasn't. It wasn't a straw poll, either. It was a LAW, and voting for it was a vote to make sure some people never get to be married to their partners.

Traditional marriage was unaffected by these votes. Traditional marriage continues to exist whether Amendment 2 or 8 passes or not, and whether you vote or not. People voting for these bans like to say that gays are trying to impose their values on others, but it is pretty clear that when you vote to exclude someone from a exercising a right, or you vote to take it away from them once they have it, you are imposing your values on them. Not the other way around. Traditional marriage was never on the table. Nobody was trying to get it abolished.

What they were voting on--what YOU voted on--was to close the door to same-sex couples being able to marry. Your marriage, the marriages of people voting for the Amendments, didn't change. Instead, our marriages became impossible.

Do you know why a lot of gay people want to get married? One of the best examples comes from your state of Florida. Maybe you read about the lesbian couple who were getting ready to go on a cruise with their kids when one of them suffered a stroke and was rushed to the hospital. You know what happened to the partner and the kids? The hospital whisked the stroke victim away, and then wouldn't let her family back in to see her. Ever. Not her kids, not her partner of 18 years. Nobody.

Do you know why? A hospital administrator told this poor woman, half out of her mind with fear and worry, that she couldn't see her dying partner because Florida was a Defense of Marriage State. That's what she said. She used the ban on gay marriage to keep an entire family from being with one of its members as she lay dying.

That wasn't an opinion. That was a cruel violation. That administrator behaved that way because she thought that's what the Defense of Marriage Act authorized her to do. She felt supported by the law, even though she misread it. She correctly intuited the bigotry and hate in DOMA statutes towards LGBT families, and she expressed that hate freely, feeling justified as she did it.

Do you know what happened then? A blood relative finally got to the hospital two hours before the woman died, and let the partner and kids in to hold her hand and say goodbye. Two hours. Those people sat in a waiting room all night long and a woman lay dying alone in a hospital room because of a "difference of opinion."

That's what many of us are afraid of. What if get broadsided by a car in Ohio on my way home to my family at Christmas, and end up in the hospital? Will my partner be able to see me and make decisions about my care? Ohio is a DOMA state, with an additional constitutional amendment worded so broadly, it bans anything that may be seen as resembling a marriage from legal recognition. Will I sit alone, in pain, while my partner is locked out? Should any of us have to worry about this kind of thing when we travel across a country where we are supposedly free to move at will?

Most people don't understand that hospital visitation is a benefit of marriage. They just assume that hospitals would be fair and kind and have good hearts and anyway, anyone with any decency would let a dying person's partner and children in to see them in their last hours.

In this case, they were wrong. And the saddest thing is, they were wrong because someone like you, Just an Opinion, thought that voting for a state DOMA or Amendment 2 was just a kind of public opinion poll. If I told you that voting the way you did would mean people were left dying and alone, full of tubes, hooked up to machines, while their families were banging on the door in vain to see them, would you still vote the same way?

I know that's an emotional appeal, but I just don't think there was enough representation in this election of the way these Amendments would actually affect people. I feel as if all these people who voted yes on these ballot initiatives think that gay people just want to run around aping marriage. I don't think they get what NOT having access to many of the most important legal benefits of marriage--and there are over a thousand of them--does to people's lives.

So I'm glad you wrote in, Just an Opinion, but I wish your opinion was more of a conviction. Because what might happen to people because of your vote is tragic.

Thursday, November 06, 2008

one hand giveth

Like most LGBTQ people in the US right now, I'm a lot sadder than I thought I'd be, given Obama's victory on Tuesday. GF and I voted a week early, which had its good and bad results. The good results were that I got voting over with, but unfortunately, that meant I was "free" to leave the city and my girls to come down to school. My Trial Advocacy class requires 12 hours of courtwatching, 8 of which have to be jury trials, and I had so far completed zip. I teach on Monday nights, so if I leave town right after class, I can get downstate sometime before midnight. There was a jury trial at 9am Tuesday morning. Ugh.

After spending Election Day sitting on hard benches (4 and a half jury trial hours, check!) that made my tailbone ache and dug into the small of my back, I ran back to my room here to see what was happening. I watched the first red state--I think it was West Virginia--go to McCain. Vermont went to Obama. I held my breath. Obama picked up a couple more states, slowly. And then suddenly the big states started going blue, widening the gap.

This was no 2000. This was no nailbiter, with assurances of victory followed by bitter, bitter disappointment. As the Obama victories started to roll in, the television anchors started getting excited. The commentary began to cut away to Grant Park, to people walking over bridges to get to the rally there. I was sitting at my desk trying to get a draft of a paper done, but I couldn't concentrate. I kept watching the news and checking the electoral totals. Back home, GF was watching with friends, who were texting me and chatting on Facebook.

You know the rest of the story. Obama began to pull away, McCain conceded, and Jesse Jackson wept. Spellman students danced. Villagers in Kenya danced. Chicago danced.

But wasn't going so well for gay marriage.

At one point late in the evening, Chris Matthews on MSNBC pointed in exultation to an overhead shot of crowds "celebrating" in the Castro. Rachel Maddow cut in. "If that's the Castro," she said, "those crowds probably aren't celebrating."

It was true. The votes coming in from California on Proposition 8 were not pretty. Matthews assured everyone that even bad news was potentially good in this instance, because the numbers showed a much more even split between the supporters and opponents of gay marriage. Maddow made a heated retort about rights actually being taken away from people, but the conversation soon shifted back to the topics MSNBC thought were more relevant to a general audience. I went to bed that night euphoric at the Obama victory, but with a pit in my stomach about Proposition 8.

After two days, the returns are in, but millions of absentee votes remain uncounted. Still, it is almost assured that opponents of gay marriage have managed to stop progress in its tracks in California. This morning, my Family Law professor spent the first fifteen minutes of class talking about how strange it is for a state to actually take a way a right it has granted, and how no state has ever had to decide the question of whether its constitution will allow people to STAY married in the event it grants, then rescinds, the right to marry, since the usual question asked of courts is whether the constitution will allow people to GET married in the first place.

Right now, I miss my family. This week feels as if it has been a month long. My little girl is just learning to sit upright in her activity saucer, and I want to watch her try to turn its brightly-colored little plastic wheels that make bells ring. She tries so hard to make it work. She can barely hold herself up, but she concentrates. There are buttons elsewhere on it with pictures of animals on them, and if you can manage to push them while maintaining your balance, they make sounds. Right now she can barely sit for very long, and her legs are so short we have to fold towels up for her to stand on, but some day soon she will make the cow moo, and the dog bark, and the lights flash bright blue under the face of the duck.

The law says that I have to pay money to a lawyer if I want to be her legal parent, because GF and I cannot get married. If we could get married, the same presumption of parenthood that fathers enjoy (even if they are infertile, and their wives use a sperm donor to conceive) would extend to me. But we cannot get married. Instead, LGBT people like me must pay thousands of dollars to adopt our own children.

In California, the courts have extended parenthood in this manner even to same-sex couples who have not performed second-parent adoptions. Here, that's riskier. So we pay, and feel grateful we don't live in hateful states like Florida, Arkansas, or Utah, which specifically prohibit homosexuals (Florida) or unmarried couples (Utah, and now Arkansas) from adopting either the children of their relationship or children from elsewhere.

I'm very, very happy about an Obama victory, but it's hard to feel excited right now. I can't wait till tomorrow, when I can drive home. I miss my family. Despite the wonderful, amazing, historic events of this past week, the world seems colder.

Sunday, November 02, 2008

the elusive butterfly

This whole Proposition 8 thing has me thinking about same-sex marriage pretty much all the time. Videos of protesters screaming at each other on street corners in Oakland circulate on gay internet blogs. People I went to high school or college with, and who now live in California, have become my Facebook friends, and their status updates grow more passionate every day. Some have reported seeing their formerly-conservative neighborhoods littered with Obama and No on 8 signs. Others are volunteering their weekends to try to defeat the measure.

In a stroke of great (unplanned) timing, this Monday in my LGBT politics and social change class we are reading about gay marriage. I enjoy teaching this class even though I am only doing it because I am desperate for cash. It takes up too many hours of my week, but the students are extremely committed to discussing the reading. This week we are going to talk about George Chauncey's "Why Marriage?" and look at the First Interim Report of the New Jersey Civil Union Commission. After that we will watch the documentary "Freeheld," about the fight of a dying lesbian police officer in New Jersey to give her partner her pension benefits.

As you probably know, Chauncey's book argues, among other things, that the LGBT community got really interested in marriage as a result of the AIDS crisis, when it became apparent how precarious the legal status of gay relationships and gay families are with respect to hospital visitation, funeral planning, inheritance rights, pensions, lease agreements, and child custody and visitation. The NJ First Interim Report concludes that establishing civil unions as a alternative to marriage fails to grant the same rights to same sex couples that their heterosexual neighbors get when they marry. "Freeheld," which won an Oscar for best documentary, shows a conservative community coming to terms with the injustice of denying a same-sex couple the survivor benefits that give financial security to heterosexual families when one partner dies.

As I watch Yes on 8 supporters railing against gay marriage because it means children will learn about gays in grade school, it is hard not to make the parallel to Anita Bryant's "Save the Children" campaign. Why does the right's fear of changing gender roles and anger towards the demise of patriarchal marriages have to take the form of campaigns to save children? From what? One white Massachusetts woman in a Yes on 8 film maintained that childhood should be a time of innocence, and that kids should wait to learn about gays until they are older. She and her husband are outraged that grade-schoolers went on a field trip to surprise one of their teachers at her lesbian wedding. They feel that being exposed to such things damages the carefree world every child is entitled to have in grade school. They feel that children exposed to such things--love, I guess--are somehow unprotected.

Watching them, I think about nineteenth-century ideologies of children as asexual angels, and I wonder if these parents also think their children should be protected from other kinds of difference. Surely going to school with children of color will only mar the innocence of white children, who deserve to grow up in an environment free from the knowledge of this country's legacy of racial violence. Ditto for children of immigrants, especially undocumented ones, whose parents will be hauled away by INS some fall afternoon. White children who are citizens should be protected from sadness like that. How about class difference? Middle-class children should definitely be protected from knowledge of poverty, since it will only make them feel sad and helpless to know how many of their peers go to school hungry each day.

These parents don't assume that their children are already going to school with the children of lesbian or gay parents, or with children who may identify as lesbian, gay, or transgender. These parents assume they can keep difference out--at least for now. It is the same logic that assumes there are no gay people next door, or in the schools already, or in your own family. It assumes that learning about difference is bad, and filthy, and traumatic. These parents never talk about why male-female relationships allow children to keep their "innocence," while female-female relationships appear somehow to be overtly sexual, even to toddlers.

Meanwhile, this Sunday's New York Times Styles section is filled with gay marriages, and the "Vows" story that serves as its centerpiece is, rarest of rarities, a gay couple with twin daughters. I think about these children, so wanted that their fathers spent upwards of 100K trying to get them. These little girls surely should be saved from such love, such difference, and their parents should never be allowed to marry and give them anything--not property, health care, financial security, respectability, love. Other children definitely need to be protected from these two little girls, who will grow up confident, secure, and "spoiled"--but not spoiled at all--from being showered with love by two doting, powerful, successful gay men.

My daughter-not powerful, certainly, but very beautiful nonetheless-- is asleep in the next room. One of her favorite toys is a big multicolored butterfly (ok, it's really a firefly, I guess) that lights up and plays songs when you pinch it, or bite it, as the case may be. My partner, who I cannot marry because it is not legal here, calls this toy the Elusive Butterfly, after the 60s song about the butterfly of love, which I taught her because when I was a very little girl I thought that song was so beautiful I would practically faint with joy when it came on the radio. I think there was something about the combination of butterfly and love that was almost too great for my soul to bear. I'm sure I learned that love in my family, especially from my mother, who was fascinated by each one of her children, and who took pains to cultivate in each of us strong sense of social justice and lifelong horror (she came from the South) of racism, snobbery, and all forms of prejudice.

My hope for my daughter is that the love she experiences with us will teach her to love other children in spite of and because of their differences, and that the deep and formative happiness of her childhood is not based on some fake innocence, but on something better than that--some kind of love of beauty and joy in the world that feels so big in her heart, it makes her want to faint with happiness. I don't want to protect her from love, or from emotion. I hope I can fill her with feeling, and compassion, and empathy, and a keen ability to perceive her fellow human beings, the generation she will spend her life traveling with. I hope her only innocence is optimism about her own ability to defeat evil, hate, bigotry, and despair.

Which we, as the generation before her, can address right now. Stop the hate. In any way that you can today, stop Proposition 8.

Wednesday, October 29, 2008

transcontinental marriage

In honor of National Write to Marry Day, a blogger action supporting the defeat of California's hateful Proposition 8. See all the links at Mombian.

I have started saying it almost every day, and I know it has become annoying. "I wish we could get married here!" Sigh. It is almost always followed by a sigh.

We have no money to get married. We can barely afford a marriage license and a City Hall appointment. But I dream about a big hall with vaulted ceilings, an open bar, a dance band, and all the people I love who support us every day just because we shack up together.

OK, it's pretty clear that I am dreaming about the party, not the wedding. I can't imagine what I'll wear. I can't imagine what music we'd play, or whether we would do a hokey walk down the aisle.

My partner is a no-nonsense girl, or at least, BELIEVES she is a no-nonsense girl. This means she eschews sentiment. "Why have a wedding?" she asks, exasperated. She says this often when I say, "I wish we could get married here!" (Sigh). She thinks weddings are expensive and stuffy and no fun, especially for the people getting married. She's happy to go to City Hall and then celebrate at a bar. But she was a Mormon, and married once. Her wedding was a restricted ceremony in the temple, her wedding night a huge disappointment. Her reception was the day after the wedding, and filled with the knowledge of impending misery. Her divorced parents spent the day not speaking to each other. There was no alcohol.

Why get married, indeed.

But I CAN imagine a party. I can imagine garlands of flowers, and people in nice clothes. I can imagine our daughter carrying the rings, or strewing rose petals, or just toddling shyly down the aisle (I guess I imagine she will already be walking).

I imagine the friends who brought us food when we were in the hospital with her showing up and dancing with us. I imagine twinkly lights and our families, who have never met, meeting each other at last.

I imagine wonderful little stuffed things to eat. I imagine martinis and champagne.

There are lots of critiques of marriage out there, and critiques of monogamy, respectability, domestication, and the couple form. They are all valid. Marriage shouldn't be the thing you have to do to get health care, or hospital visitation, or de facto parenthood, or survivor benefits, or pensions, or your lover's estate tax-free. But the fact is, if you have marriage, you can get those things, and making marriage more available begins expanding all sorts of other rights to LGBTQ people. Begins. And that's what is important.

My favorite wedding I ever attended was for graduate school friends who had a combination Christian and Jewish ceremony. As they stood under the chuppa, the Rabbi spoke about its four corners, like a roof over their heads, a roof supported by all of us supporting them in their togetherness, with four walls open to all those who loved them, and who they loved in turn. I loved the image of love as a house, not just to contain two people, but open to the winds, a space for two people be something greater than two alone.

I remember that wedding, and I wonder if I will ever have one like it, and I think maybe I won't live to see marriage for us out here, especially if hateful amendments like California's proposition 8 are allowed to enshrine discrimination into state constitutions. Still, the states continue to fall, one by one, to the neutral application of the principle of equal treatment. The Advocate this week called the cluster of northeast states with same-sex marriages and civil unions a "corridor of love" stretching from New Hampshire to New Jersey. I thought that was lovely. I prefer to think of the northeast corridor and California like two ends of the transcontinental railroad, creeping across the landscape, making the flow of love and commerce easier, uniting a divided country. There would be some sort of suitable gay ceremony, hopefully with lots of jokes about what "driving the spike" might really mean. I hope that railroad makes it here someday. I like to imagine that the driving of the euphemistic golden spike uniting both sides will happen right here, in a gay neighborhood of our very own city, and that when it happens we will feel as if our spaces are opening out into the world, beyond our houses and our selves, connecting all of us.

I have started saying it almost every day, and I know it has become annoying. "I wish we could get married here!" Sigh. It is almost always followed by a sigh.

We have no money to get married. We can barely afford a marriage license and a City Hall appointment. But I dream about a big hall with vaulted ceilings, an open bar, a dance band, and all the people I love who support us every day just because we shack up together.

OK, it's pretty clear that I am dreaming about the party, not the wedding. I can't imagine what I'll wear. I can't imagine what music we'd play, or whether we would do a hokey walk down the aisle.

My partner is a no-nonsense girl, or at least, BELIEVES she is a no-nonsense girl. This means she eschews sentiment. "Why have a wedding?" she asks, exasperated. She says this often when I say, "I wish we could get married here!" (Sigh). She thinks weddings are expensive and stuffy and no fun, especially for the people getting married. She's happy to go to City Hall and then celebrate at a bar. But she was a Mormon, and married once. Her wedding was a restricted ceremony in the temple, her wedding night a huge disappointment. Her reception was the day after the wedding, and filled with the knowledge of impending misery. Her divorced parents spent the day not speaking to each other. There was no alcohol.

Why get married, indeed.

But I CAN imagine a party. I can imagine garlands of flowers, and people in nice clothes. I can imagine our daughter carrying the rings, or strewing rose petals, or just toddling shyly down the aisle (I guess I imagine she will already be walking).

I imagine the friends who brought us food when we were in the hospital with her showing up and dancing with us. I imagine twinkly lights and our families, who have never met, meeting each other at last.

I imagine wonderful little stuffed things to eat. I imagine martinis and champagne.

There are lots of critiques of marriage out there, and critiques of monogamy, respectability, domestication, and the couple form. They are all valid. Marriage shouldn't be the thing you have to do to get health care, or hospital visitation, or de facto parenthood, or survivor benefits, or pensions, or your lover's estate tax-free. But the fact is, if you have marriage, you can get those things, and making marriage more available begins expanding all sorts of other rights to LGBTQ people. Begins. And that's what is important.

My favorite wedding I ever attended was for graduate school friends who had a combination Christian and Jewish ceremony. As they stood under the chuppa, the Rabbi spoke about its four corners, like a roof over their heads, a roof supported by all of us supporting them in their togetherness, with four walls open to all those who loved them, and who they loved in turn. I loved the image of love as a house, not just to contain two people, but open to the winds, a space for two people be something greater than two alone.

I remember that wedding, and I wonder if I will ever have one like it, and I think maybe I won't live to see marriage for us out here, especially if hateful amendments like California's proposition 8 are allowed to enshrine discrimination into state constitutions. Still, the states continue to fall, one by one, to the neutral application of the principle of equal treatment. The Advocate this week called the cluster of northeast states with same-sex marriages and civil unions a "corridor of love" stretching from New Hampshire to New Jersey. I thought that was lovely. I prefer to think of the northeast corridor and California like two ends of the transcontinental railroad, creeping across the landscape, making the flow of love and commerce easier, uniting a divided country. There would be some sort of suitable gay ceremony, hopefully with lots of jokes about what "driving the spike" might really mean. I hope that railroad makes it here someday. I like to imagine that the driving of the euphemistic golden spike uniting both sides will happen right here, in a gay neighborhood of our very own city, and that when it happens we will feel as if our spaces are opening out into the world, beyond our houses and our selves, connecting all of us.

Friday, October 17, 2008

My Classic Dames Identity

I'm so happy. I love Myrna Loy.

Your result for The Classic Dames Test...

Myrna Loy

You are class itself, the calm, confident "perfect woman." Men turn and look at you admiringly as you walk down the street, and even your rivals have a grudging respect for you. You always know the right thing to say, do and, of course, wear. You can take charge of a situation when things get out of hand, and you're a great help to your partner even if they don't immediately see or know it. You are one classy dame. Your screen partners include William Powell and Cary Grant, you little simmerpot, you.

Find out what kind of classic leading man you'd make by taking the

Classic Leading Man Test.

Tuesday, October 14, 2008

first cut

Autumn is here. At dusk, Sagittarius hoists his jeweled bow just above the horizon. School is in full swing, the nights are lengthening, and it is time for Maude to get her first round of shots.

I know that vaccinations are important. I feel anger towards people who decide to forgo them, fearing autism or some other side effect, putting everyone at risk once more for diseases that were supposed to be gone for good. Still, I understand not wanting to subject a baby to needles, and chemicals. It seems barbaric to pierce soft baby skin, and draw bright red baby blood, when a child can't even understand what is happening.

The morning of her shots Maude doesn't want to wake up at all. I run a bath for her, then take it myself, and finally, when she persists in sleeping, we gently rouse and undress her, and slip her into the warm water while she is still groggy. She doesn't cry, or even wake up grumpy, but she only opens her eyes, and submits patiently to our ministrations. As I towel her dry I think about the nurses cleaning her when she was born, and remember standing impatiently, eager to hold her. Her eyes are larger now, and something flickers down inside of them when they look at me, and when I talk to her and tease her, she breaks into sweet, toothless smiles.

Our doctor's office is 20 minutes north, in a tree-lined neighborhood that feels far away from our tired streets. We usually listen to Classic Vinyl or 80s music on satellite radio, with Margo, Darling calling out the songs as "Baby's first Doors," or "Baby's first Billy Idol." The sun streams through the sunroof, and Maude quiets down the faster we drive. When we get to the office we place bets with the nurse on Maude's weight, and she gets it closer than we do. Twelve pounds--how can it be so little, when she is so heavy in the carseat? A little barbell weighs more. My arm weighs more.

Maude is measured, too. Already she is in a competitive world. Her weight is in the 67th percentile; her length somewhere in the 80s. This is good--not too fat, not too thin, and tallish. Her head is the real thrill, though: in the 97th percentile, it is (we hope) a harbinger of SAT scores to come.

The pediatrician comes in and talks to Maude as she lays naked on the table, and Maude looks earnestly at her at makes a variety of conversational sounds. This goes on for a while, and we are a little amazed that 1) she is being so good, and 2) that she and the doctor have so much to say to each other. I feel a little jealous. I'm not sure she talks that much to either of us.

Then the doctor leaves, turning her back on the plump innocent stretched out like Iphigenia on the altar, if Iphigenia wore a diaper. The nurse comes back, and asks me if I want to hold her when they give her the shots. Margo, Darling is already fighting back tears, so I say yes, but I feel terrible about the trusting little body sitting on my lap, the little hands clenched in mine. She faces forward, and the thought comes that I am a human chair, a human electric chair, a lethal injection gurney. Silly--it's just a vaccination, I remind myself. But then the first long needle goes deep into her baby thigh, and she screams a scream so deep that at first there is no sound, like a whisper, but an awful whisper. Then it comes, a terrible cry. I see blood on her thigh when the needle comes out--bright red, fresh, oxygenated blood. There are alcohol wipes, another needle in the thigh, more soul-deep screaming, and it is over. The most chilling part for me is that the hands never vary their grip. Babies can't clench their hands in pain. My hands, though, are squeezing like mad.

Then there are sparkly band-aids, and comforting sounds. I think about the genital cuttings of different peoples, and I am glad this is only an inoculation, not a sexual marking. There will be other castration rituals to live through, other times of handing over a child to civilizing powers. She will need another round of shots in a couple months, and then another. Then she'll be done, and hopefully won't remember visits to the doctor's office as traumatic. I don't think she remembers pain yet, or cultivates aversion. Babies are slow learners in that way--proof (I'm convinced) that repression is a good thing.

Today the tears dry quickly, and the pain seems long forgotten before we even get home. We undress her, guiltily averting our eyes from the band-aids on her legs, and slip her into the softest pajamas we can find, spotted ones with a tail and a kangaroo pouch with a little baby animal in the front pocket. I tell the friend who gave these pajamas to Maude about the vaccinations, and the negotiation of betrayal one feels turning over a child to medical processes, however minor, and she exclaims, "Good thing you didn't have to have a bris!" So we aren't the only ones making the castration connection, I think. The pajamas comfort us, their softness and little baby pocket a sentimental reminder of our own goodness as caretakers. We are good parents. We only hurt her a little now so she won't be hurt a lot later.

Or at least that's what we tell ourselves. We are extra gentle, shaken with the sudden violent reminder of our violent world, the first reminder. When she is sleeping in her crib in the darkness, I sing her a sleeping song, but in my mind I see the vermilion blood spray across her pale fat thigh, and I marvel at its redness, and I think I will never forget the satisfaction of it, of knowing she had done a difficult thing, and we had done a difficult thing for her, and the horror of it. In the darkness I can taste the tiniest taste of an old, ancient and animal horror we memorialize in these everyday health measures, in the restrained sadism of even our safest and most human of rituals.

Saturday, September 27, 2008

greater than

Well, I did it. I put an Obama sticker on my car.

It's not as if I don't want Obama to be the next President. It's just that I'm reluctant to get my hopes up about his getting elected. The fact that people are wowed by McCain's choice of Palin makes me feel the way I did in 1980, standing in the livingroom of my dorm with everyone watching the election returns for Reagan. I just couldn't believe it at the time. Couldn't people see that this guy was an idiot? What was wrong with America?

So when the Palin surge happened, I looked at the Obama sticker sitting on the hall table and felt like I probably should use it. I don't think I've ever put a political sticker on my car. Even if I want a candidate to win, I don't usually identify with any of them enough to want to have them become a permanent part of my self-presentation on the road. They are all straight, all male (except for Hillary), and all againt same-sex marriage (including Hillary). Most of them say what they think America wants to hear, including pandering to Christian conservatives in a way that makes me want to throw up (Hillary most certainly did this). I view elections more as damage control than any expression of MY ideals or MY politics.

Indeed, the only sticker on my car is an HRC "equals" sign I've modified to look like the mathematical symbol for "greater than." As my friend Danny pointed out when HRC first started using the gold parallel lines on a blue field to signify what is supposed to be the political goal of all LGBTQ people, why settle for equality when you can transform the world?

As a tribute to Danny's ability to dream big, I put my "greater than" symbol on the car, hoping that it would make me dream big, too. And today--inexplicably, perhaps-- I decided maybe we could dream big with Obama. Why not? I don't actually believe he's going to change things all that much, but I'm going to pretend that he is, and that universal health care, federal recognition of same-sex families, the end of the war in Iraq, and major investment in alternative energy is really going to happen in the next four years.

In the meantime, I'm trying to get my class I'm teaching to have political discussions without getting angry, polarized, and disrespectful of each other's views. I'm teaching an LGBT history and political change class, and in my efforts to get them engaged, I think I've loosed a whirlwind. We did some reading from Eric Marcus's Making Gay History, and we watched the Four-part PBS/Channel 4 series from the early 90s called A Question of Equality. I think Isaac Julien either made it all or helped on it a lot, because it is definitely hip and decidedly not from the usual white, middle-class point-of-view that gay history usually gets told from. Julian interviewed the drag queens and gays and lesbians of color who took part in the pre- and post-Stonewall LGBT movement to paint a sensitive portrait of the dynamic relationship between coalition and difference in LGBTQ political organizations. I taped the series when I was in grad school because I thought it would be great for an LGBT studies class, and I used to teach it a lot. When GF started teaching LGBT content she used it. It got so popular that her school tranferred it to DVD, though the copy is a little washed out. In my class, as it is usually, students were really engaged with the reading and the film, but the discussion got heated at one point, with a couple of white, privileged women's studies students berating the class for not understanding standpoint theory and their own privilege. Sigh. At one point a couple of students turned on an ROTC student and asked him to defend his position on--I don't know--the war? Conservatism? I'm not sure where they were going, except that at one point there had been an intelligent evaluation of the vulnerability of radical political groups to splinter over differences. Then, suddenly, the class was splintering over differences.

I was just about to intervene in the discussion when another student made a joke about the ROTC guy speaking for all military personnel, which was a sensitive way of defusing things, I thought, and of being sarcastic about the women's studies students singling him out. Also, he seemed eager to defend his point of view, and actually argued that the class shouldn't assume everyone shared the same political beliefs, class background, or moral philosophy, which was I thought a great thing to point out.

I'm making it sound a bit chaotic, which it really wasn't, because I was making them address the issues brought up in the reading and the film, and afterwards I thought it had been really performative of exactly the kinds of differences that we were studying. Then a student with a pierced lip buttonholed me afterwards and said she was shocked, shocked! by the fact that the class had called out the ROTC guy. I explained to her that I thought the other students had defused it, and that he seemed happy to have the opportunity to explain his point of view--to which they listened--and how all in all I thought it had been a successful class, if harrowing. The student also claimed to have seen other students text messaging during the film, and even chewing tobacco. I just looked at her. While I try to make sure the class is never disruptive, I really can't monitor people very well when we are watching a movie IN THE DARK. And I laughed to myself about the tobacco. Really? Is this where student rebellion is at these days--sneaking dip during class?

Seriously, I forgot that teaching can drive you batshit crazy sometimes. And that students expect you to be their mother, or the mother of everyone else. And that they are supercilious even thought they have pierced lips. And that many of them are perfectly comfortable telling you you aren't doing your job of making them feel comfortable. And you can feel bad, because on the one hand, you want them to have a real discussion, without having be watered down and censored so that it feels fake, but you also realize that they could use a good lesson in rhetorical (and other) accommodation, and be reminded that a classroom is not, in fact, the same as a political organization. But this is exactly the reason some people love teaching women's and gender studies classes, and others won't touch 'em with a 10-foot pole.

I found this truly disturbing, because Pierced Lip and I obviously had totally different experiences of the class. I also felt disrespected, because when I passed her in the hall again, in an empty building at 9 o'clock at night, she wouldn't look at me, but instead busily texted someone on her phone. Weird.

This week, Bayard Rustin! We'll see how they do with that. I haven't taught a GWS course in so long, I forgot how heated people get, and how it can make you long for the impersonality of literature.

GF puts it differently. She says it's just hard to care, and it always surprises--and annoys--us that they do. She is being funny, of course, but there is some truth in what she says.

GF is off getting her tenure file together in a coffeeshop. Little pixie baby is asleep in her swing. After exhausting all possible remedies, including food, diaper change, mobile-watching, lying on a play mat, swinging and swaying in my arms, and singing songs, I finally settled her down in front of the Michigan State football game, and she quieted down, watched it with some interest for a few minutes, and fell asleep. I think maybe she's really just a middle-aged man trapped in the body of a baby.

Which is way better and less dangerous than being a baby trapped in the body of a middle-aged man. SInce McCain is acting a lot like that these days, I'm going to try to care about politics just long enough to get a grownup in the White House. And maybe watch a little college ball with Maude.

Sunday, September 14, 2008

a little night music

Even before Maude was born, we knew we would have to think harder about music. Margo, Darling began regularly playing Joni Mitchell and Tori Amos in the car, and at night would beg me to sing a song to her rising abdomen. I felt silly singing to a stomach, but I tried to rack my brain for something lullaby-ish that might entertain the little fetus trapped in the dark down there. When she was born singing came more easily, especially since I quickly ran out of things to say to her when she was crying in my lap, too tired and worked up to sleep. Singing is the natural response to a crying baby. It allows you to soothe yourself while soothing her. It allows you to pick a mood and insist on it.

"There's no hysteria here," a song can say. "Nobody is at their wit's end in THIS house, oh no! THIS house is a palace of mellowness." Say it, know it, be it. Eventually it feels true.

As Maude sobbed in my arms and I bounced up and down on the exercise ball trying to soothe her, I would remember the songs I listened to as a child. My father had a big console stereo when I was little, the kind with polished wood sides and a top that lifted to reveal a turntable and radio inside. It lit up inside when it was on, and there was a little oval panel that also lit up to reveal the words "Stereophonic Sound." The radio had a slide dial and warm yellow numbers. The speakers were covered with a woven wicker-type material.

My sister and I loved to sit on the floor with our heads pressed back against the speakers, letting the sound wash over us. I think one of our heads dented the wicker material in a moment of enthusiasm, because I remember a dent in the front. We probably got spanked for the dent, because it was my father's prize possession, but it is equally possible he shrugged it off. Parents are inconsistent like that.

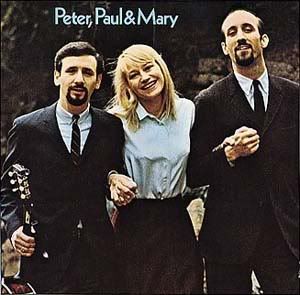

There was a lot of unhappiness, at least back then, so the stereo stands out for me as one of my happier childhood memories. My father played the Kingston Trio; Judy Collins; Mitch Miller; Big Band music; the Weavers; and Peter, Paul and Mary. He played Tony Bennett and Harry Belafonte. He loved early Beatles. He loved Patsy Cline. He loved Bread, the Mamas and the Papas, The Fifth Dimension.

My father was a moody man when we were little. My parents were high school sweethearts who had broken up when my father was in college and my mother in nursing school. He gave another girl his fraternity pin, but my mother still loved him. When she had to have a lower spinal fusion at 20 she waited in for him to come visit her in the hospital, where she lay trapped for weeks in a full body cast. Day after day she waited, but he never came. When she left the hospital she hopped a plane to Atlanta, where her father lived, met a handsome man in a bar, and married him on my father's birthday. She had two children with him before she realized he couldn't hold down a job.

My father's mother told him about my mother's divorce, and the two little girls she had. My mother and my grandmother had kept in touch. I am sure my mother told my grandmother that she had never stopped loving my father, which was true. My grandmother understood misfortune, having survived a tough childhood where she had been given away by her own father, who kept her brother but sent her out to work for any family that would take her in. My grandmother told my father to go get my mother and the two little girls that should have been his. He did.

Which is how my sister and I ended up with our little heads pressed against his stereo speakers, listening to Peter, Paul, and Mary and the Fifth Dimension day after day. At first my father thought that parenting meant beating us with a leather belt for every infraction. I remember having to come up with stories about bruises and handprints on my body for doctors during routine checkups or hospital visits. Later, when more children were born, he began to like us better, and he gave up the belt, and then gave up hitting us altogether. The years passed. We all grew up. I think he grew up more than any of us, grew into a kinder and more generous person over time. In the house of my childhood, all four of us and my parents and our dogs and cats, and horses in the barn, made what I like to call a tumbledy house, a house of noise and mess and lovely disorder and raucous dinnertime fellowship. I remember there was music in our house every night, filling in the cracks and seams between all of us like caulking, creating a reservoir of shared family life that took us all through the next decade together, and then, out into the world.

Eventually my father and I became friends. I borrowed his Tony Bennett and Harry Belafonte records and made tapes to listen to in my car on the drive home from college, and then, graduate school. He would growl at me if records went missing, but only half-heartedly, and if I had them in my possession, he told me to keep them as long as I liked. And when I played them, wherever I was living at the time, in whatever stage of my life, I recreated the raucous tumbledy house I missed, and celebrated my distance from it. The music of my childhood let me miss my family and feel free and separate from them at the same time. it let me revisit a feeling, feel comfortable with ambivalence, and make peace, ultimately, with all the bad things about growing up I couldn't change, and with all the good things I wouldn't trade for anyone else's life.

Before Maude was born I thought about how I would explain my parental relationship to her. I thought I could tell her that my father, the one whose last name I have, is not genetically related to me. I thought about how it may have mattered to me once, but never would now. I thought about how with my mother gone all of us try to see each other at least once a year, and nobody ever cares or seems to remember what degrees of blood kinship are or are not present for any of us. I thought about what a shared life is, what makes family, what it means to be a parent, or a daughter.

And so when Maude was born I sat night after night on the exercise ball, looking for songs that would soother her, and I found the ones from my childhood. I started with "500 miles," then went back to Peter, Paul and Mary for the songs I knew but could not remember. And then I found "Stewball."

"Stewball," of course, is a mournful song about betting everything on the wrong horse and regretting it. In fact, if you go back and listen to Peter, Paul, and Mary, most of their songs and the songs they cover are fairly sad: "Cruel War," "Lemon Tree," "500 Miles," "Leaving on a Jet Plane," and even--especially!--"Puff, the Magic Dragon," are songs about separation, loss, displacement, and disappointment. Did I know this when I sang them as a child? Did something in my sad little heart vibrate with the yearning, mournful minor found in that music? Or did I just think they were beautiful? Are those feelings all mixed together anyway, the beauty, the sadness, the yearning, and bittersweet memory?

Maude loves "Stewball". I can try several different songs, but "Stewball" always makes her happy. Sometimes I play it on my computer, through iTunes, and we slow dance together in the pink light of the nursery, Maude in my arms, her soft sticky cheek pressed against my face, both of us swaying softly to the guitars and vocal harmonies. I think about the heartache and the love and the yearning for safety and fellowship that is so much a part of the ideology of family, and I think about the sweet sad nostalgia I feel for a time when all of us were together under one roof, crowded and cross and driving each other crazy, but together, listening to the same music floating from room to room, humming the same songs. Surviving, fighting, changing, forgiving each other. And I tell Maude that I love her, and that I will probably disappoint her and drive her crazy, but I will try my best to give her a good life, and she is my family, now, for better or worse.

And I feel like our house, our little cramped apartment, is mellow, and calm, and grounded, and cheerful, and full of life and lots of love and all the good things that can be in a place where there is hope and the desire for happiness, and people who try to be their best selves, and love each other as best they can. Which is a lot.

Saturday, August 30, 2008

Maude has two

We are incredibly lucky to live in a state that allows second-parent adoption. This means that I can adopt Maude and become a legal parent, and have my name appear on her birth certificate, just as her biological mother is also a legal parent, with her name on the birth certificate.

When GF and I visited the lawyer before Maude was born, she told us that our state, and especially our city, seemed to be moving towards near-total acceptance of LGBT families. With the caution of one who has seen the political winds change many times, our lawyer stressed that this progress was not something we could absolutely count on forever, and that it was possible for states to roll back such adoptions and leave the status of non-bio parents up for grabs. But she told us how a conservative judge she routinely works with decided on his own that it was unfair to require a social worker to visit the homes of LGBT parents when no such visit was required of heterosexual parents. Her eyes twinkling, she said she never would have imagined that this particular judge would make such a decision, but that she had learned in her many years of practice to be surprised by human fairness.

She also told us that what we were doing was important. While we might think of our adoption as merely a personal or family decision, it was in her mind a political act to insist on the parenting rights of non-bio LGBT partners, and she applauded us for choosing to be out, proud, and legal. Finally, as a last act of personal and professional generosity, she waived half her fee when she found out I was a law student. And told me not to tell anyone she had done so.

Before Maude was born I liked to address her by name whenever possible, throwing my voice at wherever my vague sense of location imagined her to be. A thump that moved GF's belly or made it jump might be a leg, or a fist, if only I could figure out her position. I remember rubbing a hard, solid little rectangle that would float up against the roof of skin still sheltering her, somewhere above GF's bellybutton, and I thought it had to be her butt. Now that I hold her in the crook of my elbow with one hand against that hard little triangle, I know I was right. "Hey little Maude," I would croon to her. "Hey Maudie Maude." In my mind she was already, always, inevitably my daughter because I had called her, planned for her, bought sperm, strategized with GF which donors to choose and why, and called her by name, for all the long months leading up to her birth. Even now I look at her and I see my grandmother's smile, and the shadow of my own baby smile, and my sister's dark hair, and my mother's fierce eyes, and it is hard to remember that she is not actually biologically related to me. But she is mine.

She is mine when I feed her in the blue lavalamp glow of 3 a.m., and she looks at me with those bottomless eyes. She is mine when she hunches against me, trying to burp, or sleep, and rests her awkward big head wearily on my shoulder, my chest. She is mine when she snuggles against me in the morning, as one or the other of us brings her into the bed in hopes that all of us can catch just a half hour or an hour more of sleep, and little baby sighs mark her deep breathing. She is mine when she snores, and when she suffers, as all babies suffer. She is mine every time I sing her a song and her eyes close, and her head sags, and she lets me carry her past the stony gates of sleep to the rest she longs for.

Under the law, unless you live in one of those enlightened states that recognize de facto parenting (and there aren't many), a lesbian non-bio mom has no custody or visitation rights. I would have no right to guard Maude, or speak for her, or advocate as her parent, without a second-parent adoption. Now that I have one, I can access her medical records, enroll her in school, take her to the doctor, travel across state lines, and do whatever else it is that parents routinely do for the biological and adopted children they love.

All summer I read custody cases where biological mothers tried to deny visitation to lesbian ex-partners, and I answered calls from anguished parents trying desperately to see the children that they had raised from infancy, who had been taken away from them by biological moms trying to move on after a break-up. Most of these lesbian moms were heartbroken, and more worried about the children than about themselves. Most of them didn't have a leg to stand on, either.

A ballot initiative prohibiting unmarried couples living together from adoption and foster care just cleared in Arkansas. Senator McCain has stated that he doesn't believe in gay adoption, and Utah bans adoptions by unmarried cohabiting adults. These initiative just keep getting introduced every year, despite the fact that every state needs more adoptive and foster families to take in children, not fewer.

On Maude's adoption day she wore a pink sweater hand-knitted for her by an old-timey lesbian activist colleague of GF's. The sweater came with a matching pink wool blanket. She also wore a beautiful little white dress and socks made to look like little black mary jane shoes. We went into the Daley Center and waited in the family room with GF's sister and a few friends who had taken off work. One of the friends had made her the gift of a college fund. Another had turned over the invoice to me for a freelancing project she actually had done herself, and had thus paid for the entire adoption.

At one point an official leaned over the counter and tapped the sleeping baby with official papers, thus serving process telling Maude that she was required to appear in court. She never even woke up.

GF and I stood before the judge and he asked us our names and occupations. He asked our friends if we would be good parents. He admired the baby. I was nervous because I had just signed a paper stipulating that we were of good moral character, and financially able to raise a child. GF and I had looked at each other, mouthing the words "lie" and "lie" as we waited for the judge. The court seemed to treat these words as mere formalities, but I wondered at their presence in the documents. What would happen if they were ever activated? What in the world was good moral character? Does anyone have enough money to raise children these days, really?

It was a lot like being married by a JP, or at least what I imagine it would be like to be married by a JP. It was jocular but bureaucratic, stately but mundane, a little like a wedding and a lot like getting a driver's license. Sometimes it was bizarre, as when the incredibly crusty bailiff took my fingerprints and warned me, with a straight face drained of all amusement, that now that I was in the system, I had better wear gloves if I wanted to take up a life of crime. He also lost all cognition trying to take down my vital stats. "Hair . . .color?" He asked, clearly flailing in deep waters far beyond his meager social abilities. "Brown?" I queried back, unable to say for sure. Brown under all that blonde, perhaps. Or perhaps the truth of my hair was simply what it appeared to be, or what I said it was. I should have said blonde.

There are many ways that the law can make LGBT people feel like liars, like imposters. It tells you that you cannot marry in the eyes of the federal government, even though you may feel married and act married and need the benefits of marriage for your lover and your children. In many states--Michigan is one--it can tell you your children are not yours if you are a non-bio LGBT parent. In many states it will not recognize that you have changed your gender to fit the truth of your life.

When the law recognizes you, on the other hand, it can make you feel coherent and validated. The other day it told me I was a parent, with responsibilities and rights over the daughter I had helped plan, conceive, and care for. Our lawyer said as much when she took pains to emphasize the language to me of the temporary custody order granting me parental rights until the final adoption went through. In Daley Plaza there is a Picasso sculpture that soars heavenwards, a kind of beast with its legs on the pavement, wearing its strange mask, with mandolin wings and a harp for a heart, towering over pedestrians in the crisp morning. I stood in its shadow and I felt my spirits rise. I think I will always remember how tall I felt that day after our adoption, standing in the sun, still unbelieving, next to my stroller, my partner, and my little, my most beloved and cherished new daughter.

Mine.

Monday, August 18, 2008

maude's ocean

She cries, and the sound stabs the night. It is time for a night feeding, and one or both of us rushes to soothe her. Sometimes she wakes up in pain, from gas in her still-developing digestive system, and her cry is angry, desperate. Sometimes she is hungry, and her cry is clear and hard. When she is uncomfortable from a diaper, she whimpers restlessly. When she is lonely and wants to be picked up, she wails in short little bursts.

I know some people are driven crazy by the constant cries of newborns, but right now, Maude's cries just fill me with pity and tenderness. Why, why, little one? Why so much sadness for just a meal, or a diaper? I toss her a little, up and down in the way she likes, to startle her out of her jag. I say her name over and over. It often works, and she stops crying and gazes long at me with her dark, expressive eyes. She doesn't want to have to cry, any more than we want to have to listen to it. It's a terrible job she's been given, and her mute look tells me there are no hard feelings, just limited means of communication.

Yesterday she grew angrier and more desperate, waiting for food that was a little long in coming, and when I kissed her eyes I tasted salt. "She cries real tears," I reported to GF, and she told me it was a kind of baby milestone. Crying real salt tears means you are growing up.

In the night I change her one-handed, holding a bottle in her mouth while trying to wipe her clean and fasten a new diaper. I wrap her and sing her songs--mill songs, mining songs, slave songs, Christmas carols. If she likes a song she grows still and listens with her whole being. Her face locks into one expression and her eyes grow dark and far away, yet rapt. Maude loves music, and strains even now to recognize songs she knows.

She has a "sleep sheep" that plays white noise for her--rain, a stream, the ocean. The sheep is a traveling model, one with velcro straps to fasten to a bassinette or a stroller on the go. When she has eaten and been changed, she is rocked and bundled, and we sing her songs, and eventually, carefully lower her to her bed, where we turn on the sleep sheep. The ocean crashes over her head and her feet in the little bed, the ebb and flow of the waves hissing back and forth in a round hollow echo in the darkness. I wonder if the ocean is for her, or for us, imaginary waves breaking on the shores of our rental bedroom, in a city far from the sea.

We are from the coasts, one of us from each side, meeting in the middle of the country. Sometimes I think of the nineteen-seventies country childhood I had, with fields of tall summer grass hot with the sun and tall sticky pines trees to play in, roll in, climb, smell, and dream by, and I could weep for Maude and her programmed urban future. Will she ever know a summer week in York Beach, Maine, running from the icy salt waves on the barren coastline that was my childhood ocean? Will we take her to swim in the hippie swimming hole that is a bend in the river in Sandwich, New Hampshire? Will she know what crickets sound like? And horses--what if she is horse crazy and I, unlike my parents, don't have an acre of field to fence in for a 4H horse for her to buy with her babysitting money?

The sleep sheep blows a dream of oceans into her ear, and I remember what it was to choke on Wordsworth when I tried to explain him to a class of Florida freshman ten long years ago. Then it was homesickness for New England that made my eyes tear up when I tried to explain what he meant by:

Hence in a season of calm weather

Though inland far we be,

Our Souls have sight of that immortal sea

Which brought us hither,

Can in a moment travel thither,

And see the Children sport upon the shore,

And hear the mighty waters rolling evermore.

Now I think it is also some sense of calm trust, some sense of knowing the way the world works, and feeling the interconnectedness of all things, that Wordsworth's speaker misses when he speaks longingly of the ocean. How far I feel from the ocean sometimes, here in the middle of the country, far from the coasts, far from home. Deep in the middle of life, it seems like a long way back to the beaches of childhood, to quiet contemplation and a peace beyond words, to the origin of things that is the ocean.

In the quiet night, though, my child cries and I hold her and comfort her, and it makes me feel oddly calm. She is simple right now, and her simplicity makes me simple too. All that matters is food, and sleep, and comfort, and trust in the arms that are there to hold you through the dark hours. The sleep sheep sings its salty ocean song, breathing the waves of my childhood, and maybe hers, in the early hours of morning. I like the sleep sheep, for all its artifice. It is a bird that sings of Byzantium. Maude is my immortal sea, and I am the waves of her ocean, patient, rocking her body until she trusts her eyes to close. It is still night, and Maude, the sheep, and I rock together to the sound of waves.

Saturday, August 02, 2008

she is born

At 6:30 a.m. on Friday I woke to GF chirping something unintelligible from the bathroom. The fans were going in our bedroom and all I could hear was something about "water." I got up and went in. She was sitting on the toilet smiling. "My water broke!" she said. I said something lame like "oh wow!"

My first thought was coffee, because I'm a selfish caffeine addict. Her first thought was to call the hospital. They wanted her in immediately.

This wasn't the way we'd planned it.

I don't know what exactly I thought would happen, but I left work on Thursday fully expecting to go back the next day. My desk was a sea of paper punctuated by half-empty diet coke bottles. I know due dates are approximate, but I think I really believed the old wives' tale that first babies are late. I think I thought we'd spend the weekend at the beach.

When the hospital told us to come in, my heart sank. I was excited, but I also knew that labor lasted for hours, and the standard advice in all the birth books is to wait as long as possible at home, relaxing, before heading to the micromanaged zone of Labor and Delivery. Still, when the bag of waters breaks, the risk of infection increases, so off we went. It was a sunny day, there were no contractions as yet, and we had time for showers and coffee and bagels.

We arrived at the hospital and the valet took our keys. It still felt like we were pretending. Did someone else have to park our car, really? GF wasn't in labor. She could walk just fine. There was no emergency. No police escort was needed.

By nine we were checked in and I began calling and texting the news. Some of our friends got so excited they called in sick to work and camped out at a nearby house, watching movies together and making plans. We thought we'd have a baby by nightfall.

As the morning passed, though, there were still no contractions, so the nurses started GF on pitocin to get things going. By early afternoon her contractions were strong enough that she asked for the epidural, and by late afternoon she was dilated four centimeters. The doctor came in to visit and see how things were going. She had switched shifts with the other ob-gyn when she heard GF was in labor. I love this doctor. When I first heard about her--that she could be brusque, that she was a good labor coach, that she kept her patients from tearing during delivery, that she was an older lesbian with a partner and kids--I just knew she would be our doctor. "That's her," I told GF. Now she teased us and laughed when I told her the hospital was like a casino because it was impossible to know what time it was or how long you'd been there once you were in one of these delivery rooms. She told us she'd see us soon. We agreed.

That's when things began to slow down.

As the anaesthesiologist explained the epidural process to her, GF peppered him with questions. Should she walk? Would her legs go numb? Could she lie down flat? And last, what if the medicine ran out before she had the baby?

The anaesthesiologist chuckled. "This lasts eight hours," he told her. "You'll have a baby before this runs out."

That was at three o'clock in the afternoon. At seven there had been little change, and I phoned the friends who had skipped work to tell them the baby might be later coming than we had supposed. At nine there was still no change, and the doctor upped the pitocin. At two in the morning, GF was finally dilated to eight centimeters.

Great! We thought. Only two more to go!

At this point the epidural had begun to wear off. GF was all for letting it end so she could feel the contractions and visualize her body opening up. The doctor reminded her that she still had two or three hours to go before she got to ten centimeters, and that when she got there she would have some hard pushing to do. We decided to get some sleep, GF started the epidural again, and we turned the lights off in the room.

At 5 a.m. the nurses woke us and the doctor told us to get ready to push. I woke up out of my chair, washed my face, and realized I hadn't eaten anything for twelve hours. The nurses brought me a turkey loaf sandwich on wheat bread. I remember GF putting a little mayo on the bread, squeezed from out of one of those little packets. She was naked from the waist down, propped up in the bed, fixing my sandwich. Even better, she started to push, and in between contractions, I ate my sandwich.

The contractions started coming fast. I could see them coming on the monitor by the bed, the numbers rising and falling with each peak and ebb. When the numbers began to go up, I would grab one of GF's legs with my right arm, put my left arm around her head, and she would pull into a crunch position and push as hard as she could to the count of ten. Then she would lean back, take a deep breath, and crunch again for another ten, and another. Each contraction had three sets of ten crunch-pushes. We did this for two and a half hours.

At 7:50 a.m. the doctor felt for the head and muttered something about it being too big. GF mentioned that our donor was 6 feet one, and I thought the doctor was going to explode. "Six one! Six one!" she spluttered. "A woman your size has no business with a six-one donor!" GF whispered that they didn't really let many short men donate sperm, which is true, and the doctor shook her head. "I want you to give one last big push," she ordered. "And I want this one to be the biggest, hardest, most productive one yet."

Now, GF is a strong little woman, and she wanted to please the doctor, and she had been pushing so hard and with so much effort her face was red and her legs shaking. But still she pushed with all her being, pushed so hard she groaned, pushed as if by pushing this one last time she could finally turn the tide and bring this baby down.

The doctor felt again. It was no good. the head was still too high. "The baby's head is getting a cone shape," she told us. "The back of the head is trying to get down the birth canal, but the major bones of the head still have to come through. I'm comfortable using forceps in situations like this, but I'm not comfortable doing it here." GF and I didn't even have to confer; we looked at each other without a word and she told the doctor a caesarian was fine with her. I felt my throat tighten and my eyes sting, not because I was committed to a vaginal birth, but because it seemed like so much to put GF through abdominal surgery after twenty four-hours of labor. Plus operations are scary. Plus I've seen too many ERs and Grey's Anatomys featuring dead delivering moms not to think anything could go terribly wrong at any moment no matter how routine the procedure.

I kissed her goodbye and they brought me blue paper scrubs to put on. When I got to the operating room I saw GF, strapped down in a crucified position with her head sticking out of a tall blue tent. Her teeth were chattering uncontrollably from the anaesthesia. She looked more tired than I've ever seen her look.

I took a seat by her head and waited. I heard the doctor discussing the incision with a resident, then I heard her call my name. "Stand up!" she said. "Come see your daughter be born!"

I ran around the tent just in time to see GF's stomach looking like a Thanksgiving turkey, and then a flailing baby with an impossibly thick white umbilical cord pulled out like stuffing and hoisted over the table, dark red and covered with what looked to be a thin layer of goat cheese. The nurses brought her to a table and started to dry her off. I touched her and called her name, and she stopped crying and cocked one dark eye at me. The other one wouldn't quite open, but the more they dried her the wider it got. Two dark black eyes looked me over from under a thick dark head of hair. She pursed her lips. "Hello Maudie," I whispered softly. "She's responding to your voice," the nurses told me. They gave me scissors to trim her tough little garden hose of an umbilical cord, then wrapped her up tight and handed her to me. I brought her over to GF to kiss.

GF gamely kissed the baby, and then went back to throwing up into a pink plastic container. Nurses and doctors offered their congratulations and I thanked them. Our doctor came towards me, her eyes merry over her surgical mask. "Well congratulations!" she said, reaching out her hand. I opened my arms to hug her. She bent towards me, and I gave her a big kiss on the cheek of gratitude and relief. She chuckled.

SInce then every day with Maude is new and strange. When she cries we've twirled her in the night, sung her songs, made up rap poems about who loves babies (Everyone loves babies), and looked deep and long into her dark, otherworldly eyes. Sometimes she looks back at me, and I see that she's come from a far place to be with us, and I fall in love. The three of us move in the house now through the long afternoons and cool evenings, all of us just looking at each other, over and over. And life feels perfect.

Wednesday, July 23, 2008

my hero

I'm not sure why I never read David Copperfield. Blame professors eager to shake up the Victorian canon. Sure, I knew the hackneyed first chapter title "I am born," and dutifully laughed alongside teachers who made fun of a narrator first person-izing his own birth. But David Copperfield was another generation's "Dickens novel," as Hamlet was another generation's "Shakespeare play." My Shakespeare was Lear, over and over, and my Dickensian narrator was Pip, over and over. At some point public opinion shifted to Great Expectations as THE Dickens to teach, probably because it is shorter, no doubt because Miss Havisham provides such a Sexual Revolution-era cautionary fable about the down side of letting your girl parts get too melancholic and cobwebby. Imagine my delight, then, to first encounter, in my mid-forties, the mannered yet modest cadences of young Copperfield, left alone in the world without parents, property, or prospects. Pennyless but for the unconditional love of his good nurse Peggoty and the gift of his own generous and self-improving heart.

I think I love him for his optimism. While the serialization of the novel means there are too many quirky-yet-heartwarming moments for my taste (the characterization and verbal tic equivalent of Disney's rolly-poly animals and birds with long lashes), there are enough brutal patriarchs and brutalized women that I appreciate David's faith that things will--must--get better. I thought when I opened the pages of the novel and began reading during my morning commute that I would sink into the rhythms of Victorian London, forgetting the sway and squeal of the train, the smell of the bodies of my fellow passengers, how tired and unready for the day I often feel. Instead the present and the past tumble together, and I am riding in a carriage through the dark passages of my own life, following the thread of a voice whose story leads ever upwards into a place of arrival, like the escalator I ride every day up, up from underground into the wide white bustle of the urban morning. I wonder, as David does, whether I will be the hero of my own life, even now, every day in the story where I find myself. And I can't help hoping, as I hear that wonderful narrative voice turning and rolling in my head, word piled on word, confident of a reader out there who can hear and be delighted by it still, that I will be.

Thursday, July 03, 2008

waiting game

Midsummer blooms like a tigerlily, and with it come the longest afternoons of the year. Our livingroom is cool, our windows caressed by bright and dark leaf shadows. Outside a lawnmower drones like an insect, and the UPS man buzzes the front door. Today our diaper bags arrive. Mine is a green messenger bag with purple flames. Hers is a Chinese red with orange flowers. The cats eye them with interest, as new scratching pads.

We are waiting, waiting for the Little Nipper. Margo's belly is huge, jutting out in front of her at a right angle. Now it sails before her, its fleshy prow impossible to minimize. Even the largest maternity top makes it look as if she is wearing a tablecloth, because the the distance between the bottom of the shirt and her body is so great. Yesterday she ran away from the neighbor across the street whose garage we rent, because he is an old man, and Margo doesn't feel like answering questions about being pregnant. Last night I laid a fork on her belly at the top of it, where it plateaus, and she asked me tartly whether I was trying to be funny.

Sometimes she wants soft serve at 9pm. Sometimes I come home and she is in tears. This afternoon I found her happily working on her book, lying on the couch, her shirt pulled up to expose a vast, undulating dome. Her torso is a crystal ball inverted, its clouds and shadows pushing from within. We sit and gaze at it, resting our hands on its sides, asking the baby in there our ouija questions.

When I am at work she text messages me her ideas about labor and delivery. Today she asked whether I thought "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?" would be a good distraction movie. I thought it was an inspired choice. In the movie the childless academic couple who terrorize new faculty after a late-night party by drinking themselves to viciousness and playing Hump the Host refer to their imaginary son as the Little Nipper. I sometimes think we decided to have a baby so as not to become this older academic couple, drinking too much, nagging each other, creating bitterly destructive parodies of heteronormativity in order to re-animate the dying embers of our relationship. Other times I think we just wanted something more simple and joyous than work in our lives, because children make you remember feeling hopeful.

For now, we wait. The air is cool as the early evening comes in. I type at the keyboard, wondering when the baby will come, and how it will change our lives. I think about the drowsiness of middle age, and the peace we know now, and the clamor and noise and activity that our lives will take on soon. The cats crouch at my elbows, eager to be fed. Margo dozes on the couch, her head drooping on the pillow, dreaming of grace.

Thursday, June 26, 2008

Friends don't let friends seek this

Here's another one for the archive that made us laugh today: